- No products in the cart.

The Algarve is a place where the sea has always been more than just a line on the horizon. It’s a deep, longstanding relationship. For years, fishermen and the canning industry have brought the Atlantic to the world tables, turning sardines into a symbol of the Portuguese and Algarve people. However, the history of the canning industry is not just a tale of success; it’s also a story of struggle, adaptation, and, at times, a lack of freedom.

Before April 25, the canning industry was a pillar of the economy and society. Canning factories were scattered across the country along the coastal areas, employing thousands of people. The galleons returned, laden with sardines, signalling the start of a busy factory routine. Men and women, especially female workers, would spend hours processing the fish and placing it in cans to be shipped worldwide. Productivity was high, but the context in which this production took place was not always fair or free.

During the Estado Novo period, the freedom of those in the canning industry was limited by the centralisation of power within the regime. Control over production and exportation was strict, with prices set by government bodies. Industrialists had limited opportunities for innovation, and new technologies were restricted, such as the installation of freezing chambers or the use of modern techniques. In this case, freedom wasn’t just about the ability to negotiate but also the autonomy to evolve and adapt to changes in the global market.

During the Second World War, Portugal, as a neutral country, used its strategic position to support the Salazar regime. The canning industry became a bargaining chip between the warring powers, with canned goods sold to England and Germany. The need for resources, such as tinplate (used to make the cans), meant that collaboration between the government and the canning industry was crucial to the sector’s operation. In times of war, canned goods became not only a foodstuff but also a symbol of resilience and an economy that, despite being controlled, continued to function.

But the spirit of the country is far from lost. Its connection to the sea is still very much alive, now taking on a new, more artisanal form with a fresh and innovative approach. In recent years, a new generation of the canning industry has emerged. Without losing sight of the essence of what the sea means to the coastal regions, they have begun to reinvent the industry. By using traditional production methods and incorporating the quality and freshness of local products, these small canneries are recovering what once seemed lost. The technique of “handcrafted know-how,” where each tin is carefully prepared, has been key to the success of this new wave of preserves.

In the Algarve, we now have a new canning industry that stands out for its innovation, respect for the genuine taste of fish, and commitment to quality. The canned goods emerging from these new factories are not just food products but stories, traditions and, most importantly, a celebration of freedom. A symbol that, more than 50 years after the revolution that brought us freedom, the desire to create and do things well continues to thrive. The Algarve, once a pioneer in canned food production (with the country’s first canning factory founded in Vila Real de Santo António in 1853), now plays a key role in the industry transformation that refuses to disappear.

In the end, the sea remains our greatest ally. And, as always, it challenges us to overcome difficulties and learn from the mistakes of the past. The future of the canning industry is uncertain. Still, we can look to the sea with confidence, knowing that, even in its unpredictable waters, there is always room for new opportunities.

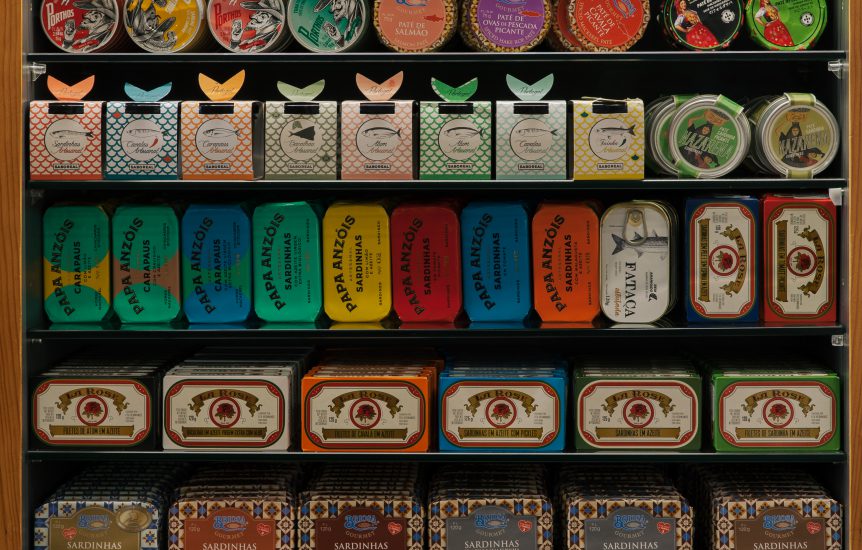

At Mar d’Estórias, we have a little corner dedicated to the canned goods that preserve the taste of Portugal. They are not just a quick treat for busier days; these canned goods have their stories and are part of the legacy of a people who, over the centuries, have known how to turn the sea into food, memory, and resilience.